The future of living wages and living incomes: An ALIGN series

You may know ALIGN as a guidance tool to help you achieve living wages and incomes in your agri-food supply chain. Making such a contemporary tool a reality required a deep digging into the past and anticipation towards the future. And that journey for us has been nothing but an eye-opener. With such amazing insights at hand, we are beginning a new blog series with facts, ideas and thoughts that shapes up the past, present and future of living wages and incomes! Now, are you ready to join this exciting journey? In this final instalment of the series, we will talk about what needs to change for a better future – a resilient food supply chain post-COVID, policies that favour migrant workers and using technology to shape a transparent value chain.

This is the final instalment of a three blog series. Read the first chapter here and the second chapter here.

From a mere ideology in Ancient Greece to research that studies the concept distinctively, from objections in factories to campaigns that shook the world, from defiance of Keynesian theorists to modern-day neo-liberals; the concept of a living wage and income has gone through years of struggle to prove its righteousness in this world.

While recessions, world wars and industrial slavery became top-notch reasons to implement living wages and incomes in this capitalist world, the year 2020 brought in another catastrophe to vindicate a fair wage; the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an employment crunch that is 10 times worse than the 2008 Financial Crisis, with devastating repercussions for the food sector.[1] The crisis brought out the realities of disrupted food supply chains, increasing hunger and malnutrition and more importantly the suffrage that farmers and their families around the world live through.

COVID-19: A wake-up call for living wages and incomes

It’s no exaggeration to say that COVID-19 has been a seismic event in the lives of every actor in a food supply chain. But it is also an unerring fact that the repercussions have been the worst for the less-wealthy in the chain.

For farmers in low, middle and high-income countries alike, the pandemic has translated to poverty, the inability to feed families and sometimes even suicides.[2],[3] For instance, in India, where more than 50 percent of the population is employed in the agriculture sector, the government has abysmally failed to protect the workforce with an increase in prices of fuel, fertilizers and insecticides even amid the pandemic. In early June, the government also used its executive powers to push the privatization of agriculture with false promises that farmers will get greater freedom to sell their produce outside large agricultural markets taxed by state governments. But very soon these farmers realised that it only created a monopoly for corporate buyers rather than empowering them. The lockdown has also robbed side jobs from most of the farmers, and all of it together resulted in crippling debt and abuse of land.[4] The situation is no better in the world’s superpower nation and largest exporting force, the USA. Money is tight and more food is wasted than ever as farmers are no longer able to send their produce to processors due to lockdowns. Another result of the crisis you may not have seen coming: a lot of farmers also experience PTSD from having to kill off so many of their animals.[5]

Why the world should watch the Indian farmer protests very closely

Read our guest blog by food policy analyst and journalist Devinder Sharma, who visited the farmers’ protests. He explains why these Indian farmer protests concern us all.

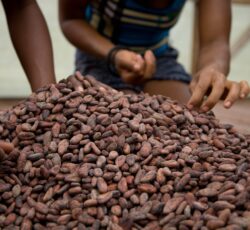

To make matters worse, COVID-19 has exacerbated child labour in the food sector, which already accounted for more than 70 percent of the world’s child labour.[6] The phenomenon is now at threat of further increasing as economic difficulties faced by the children’s households are likely to put them in harmful and unacceptable conditions.[7] An example from the Ivory Coast shows that a 10 percent reduction in income, due to a drop in the cocoa price, led to an increase in child labour by more than 5 percent.[8] Moreover, this disheartening effect can also result in gender inequalities, with girls being particularly vulnerable to exploitation in agriculture and domestic work. The Malala Fund foresees a similar pattern as was seen during the Ebola crisis, where girls were exposed to sexual exploitation, teen pregnancy and early and/or forced marriage as well as child labour.[9] What is not helping is that the majority of these child labourers work as unpaid (family) labourers without formal contracts, making it extremely strenuous for social auditors and certifiers to pick out in the supply chain.

The ignored population of migrant workers

When talking about a living wage, it is important to have the prospects covered for migrant workers too. It is often the case that immigrants and temporary migrant workers end up earning much less than a native worker under the justification that accommodation and transportation are provided to them. However, these inputs are often not documented. Furthermore, labour contractors typically deduct a significant percentage from migrant workers for their ‘services’, and this illegal deduction depresses their wages below the legal minimum.[10]

Ricardo Salvador, senior scientist and director of the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists gets it right. He says that the ‘agriculture and agri-food sector exploits individuals who are economically desperate and willing to tolerate conditions that others will not.’ This means that the most dangerous and low-paid work is done by Indigenous people and people of colour, undocumented migrants, refugee claimants and other low-income communities.[11] As Niel Coleman, Co-Director of the Institute for Economic Justice, recently said during the five-year anniversary of the co-working platform Living Wage Lab: making sure a living wage is achieved is not just about financial gains but a way to win back dignity of these people and a confrontation to the racial inequalities that have dominated this world for centuries.

Anticipating the future: the promises of technology

Unfortunately, the paradigm of the white saviour is not absent from the living wage discussion, which often takes place without the participation of the ones most affected: the producers and the workers of the supply chains of this world. These people have a voice with valuable insights for the process and it is time for this voice to reach the white upper class’ ears deciding about their livelihoods.

The spread of technology to the four corners of the world has created the conditions necessary for a future where the voice of each and every link of all supply chains can be heard, registered and used to improve sustainability goals. For one, the potential of digital tools for empowerment is being explored by Solidaridad, which has developed apps providing insightful information to farmers.[12] In the same way, farmers using their phones can voice their concerns and issues, make known any human rights violation and verify if they are receiving what they were promised. In combination with blockchain technology, the implementation of initiatives like Solidaridad’s could create a trade world with producers and workers being the agents of change, raising their voices to combat the source of their issues.

Blockchain? Yes, blockchain. As more and more companies and various stakeholders acknowledge the importance of paying a living wage, it looks like the main challenge to tackle in the near future will be to make sure such promises are actually implemented. The level of complexity which characterises today’s globalised long supply chains feeds one of their key weaknesses when it comes to sustainability: a lack of transparency. If any goal is to be achieved regarding such systems and living wages, however, addressing this weakness must be a priority.[13] Therefore, the future calls for 100 percent transparent supply chains. Impossible? Well, blockchains are here to state the opposite, paving the path for a completely transparent future. This technology refers to the registration of financial or any other specific information throughout a supply chain in a transparent manner, linking each and every one of its links. Blockchain is basically a tool of proof, in our case proof of paying a living wage, which allows for companies to support their sustainability claims with facts. How’s that for a better tomorrow?

Crises, wars and recently a pandemic – all of these have revealed to humanity that they are a highly interdependent species. What happens to one person can soon affect many others, even the ones on the other side of the planet. This interconnectedness is especially strong in global supply chains – when food processing industries in China shut down, it can result in hungry stomachs in a poor farmer’s household in Africa. This understanding is now encouraging a serious assessment of our social, psychological and economic institutions. At the core of this transformation is the need for systemic changes in the basic amenities of human lives. The right to access work that pays a living wage or income provides health care and offers humane conditions.

This is the final instalment of a three blog series. Read the first chapter here and the second chapter here.

Want to learn more about reaching living wages and incomes in your own supply chains? Go to the website of ALIGN for a step-by-step guide.

Text and research by Aswini Harinath and Kyriakos Mouskos.

Want to learn more about reaching living wages and incomes in your supply chains?

Read the ALIGN series …

[1] Nagarajan, S. (2020). The COVID-19 jobs crunch is already 10 times worse than the 2008 crisis, and a 2nd wave could leave 80 million people unemployed by the end of 2020, OECD warns. Markets Insider. https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/oecd-warns-double-hit-scenario-caused-second-coronavirus-wave-2020-7-1029373233

[2] FAO (2020). Farmers and agribusinesses at risk under COVID-19: What role for blended finance funds? http://www.fao.org/3/ca9753en/CA9753EN.pdf

[3] Singh, K. D. (2020). ‘The Lockdown Killed My Father’: Farmer Suicides Add to India’s Virus Misery. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/08/world/asia/india-coronavirus-farmer-suicides-lockdown.html

[4] Singh, K. D. (2020). ‘The Lockdown Killed My Father’: Farmer Suicides Add to India’s Virus Misery. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/08/world/asia/india-coronavirus-farmer-suicides-lockdown.html

[5] Plescia, M. (2020). “Fall-off-a-cliff moment”: Covid-19 adds harrowing new dimension to farmers’ stress. The Counter. https://thecounter.org/farmers-stress-mental-health-agriculture-covid-19-culling-pigs-milk-dumping/

[6] FAO. (2018). Child labour in agriculture is on the rise, driven by conflict and disasters. http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1140078/icode/

[7] International Labour Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund, ‘COVID-19 and Child Labour: A time of crisis, a time to act’, ILO and UNICEF, New York, 2020.

[8] International Cocoa Initiative. (2020). The Effects of Income Changes on Child Labor: A review of evidence from smallholder agriculture. https://cocoainitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ICI_Lit_Review_Income_ChildLabour_15Apr2020.pdf

[9] Malala Fund. Girls’ Education and Covid-19: what past shocks can teach us about mitigating the impact of pandemics. https://downloads.ctfassets.net/0oan5gk9rgbh/6TMYLYAcUpjhQpXLDgmdIa/3e1c12d8d827985ef2b4e815a3a6da1f/COVID19_GirlsEducation_corrected_071420.pdf

[10] Fair Labor Association. (2017). Fair Compensation for Farmworkers in Global Agricultural Supply Chains: Emerging Good Practices and Challenges. https://www.fairlabor.org/sites/default/files/documents/reports/fair_compensation_for_farmworkers_good_practices_and_challenges_february_2017.pdf

[11] Salvador, R. (2020). Agribusiness Is Using the COVID-19 Crisis to Slash Food-Worker Wages: three ways you can stop it now. Heated. https://heated.medium.com/agribusiness-is-using-covid-19-crisis-to-slash-food-worker-wages-1024552fc1df

[12]Solidaridad (2020). Engaging Producers with Digital Tools. https://www.solidaridadnetwork.org/news/engaging-producers-with-digital-tools

[13] Ethical Trading Initiative. (2017). Towards Greater Transparency: The business case. https://www.ethicaltrade.org/sites/default/files/shared_resources/eti_transparency_business_case.pdf