Foodpact 4: our responsibility to the workers

At Fairfood, we love good food. We’d also like the people who produced our food to be able to afford a proper meal. Doesn’t sound like a very big deal, right? Yet it seems to be. In this new blog series, we’re investigating why and, more importantly: how we can solve this. This time: our responsibility to the workers.

Tea is not something I have delved too deeply into – I’m more of a coffee drinker myself. But after an afternoon with Faiham, I must admit I was chiding myself over how little I knew. Faiham Ebna Sharif is a photographer and researcher based in Bangladesh who has been photographing tea workers in the Sylhet region of Bangladesh for the past three and a half years as part of his Cha Chakra: tea tales of Bangladesh project.

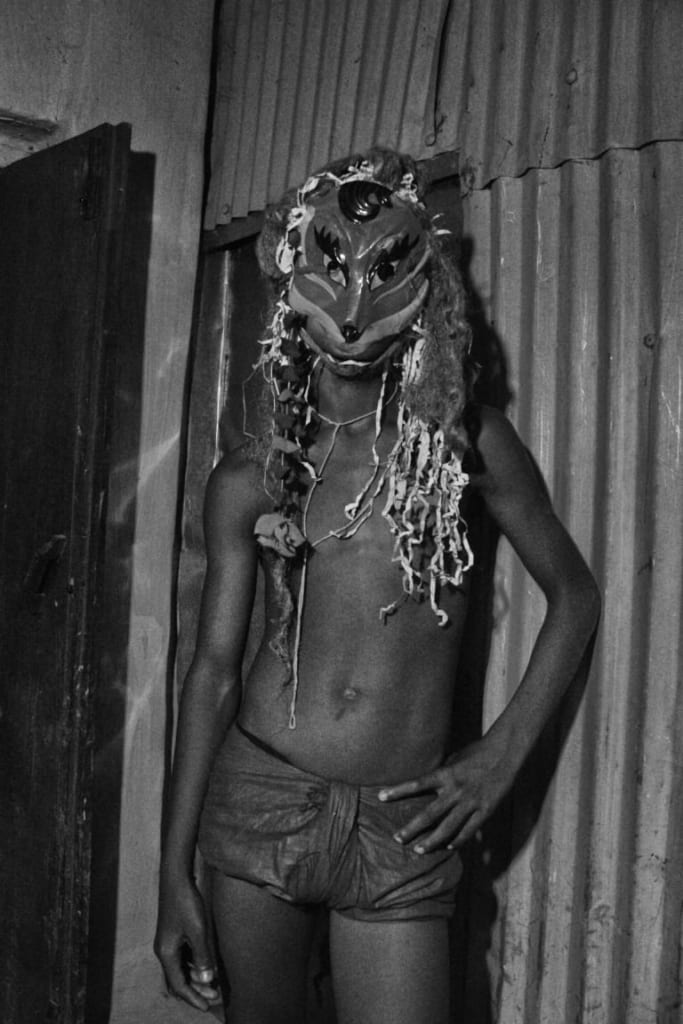

Faiham’s relationship with tea has been a long one. As a child, the staff at his school came from the tea workers’ community and the school was surrounded on one side by tea fields. As an adult, his interest in the lives of tea workers grew. “Once I went to the tea garden as a journalist”, Faiham tells me. “And I found the hardship and at the same time an interesting link between the tea drinking culture and the life of the workers, which is mostly unknown to people. Then I thought I would love to tell the story.” Faiham is providing the outside world with an honest glimpse into the lives of these tea workers. He approaches his work in an ethnographic way – living, eating and sleeping with a family from the community. In this way he is able to connect with the community on a deeper and more organic level, and connect the workers’ lives to consumers in Bangladesh and the rest of the world.

A striking text on Faiham’s website: “Ethnicity of 80 different communities and their diverse religious believes within the workforce are probably the reason the tea workers are discriminated against. Hence the ‘aura’ of the centuries old feudal structure is still evident in the ‘estates’ as a form of master and slave relation. With 85 taka a day (Just over USD 01) and other marginal benefits, a permanent worker in a grade one garden, has the most ‘secured’ life according to the law. Poor access to accommodation, education, healthcare and sanitation system, safety at work, gender discrimination and most of all, extremely low wages – all these exploitations complement a theoretical frame work that produces the cheapest labor in the global economy. Yet, tea is the second most consumed drink after water around the globe.”

Beyond putting these issues on the table, Faiham’s work has brought about real changes to the lives of some of the workers. Faiham provides an example of an instance where a tea worker who had lost his hand in an industrial injury was attending a photo exhibition of his. Also at this exhibition was the Secretary of Ministry of Labor and Employment. She was particularly struck by this man’s story because she happened to be the one to sign the papers for his work on the tea plantation, but was unaware of these incidents. She encouraged Faihman to reach out to her if he encountered other workers with work-related injuries.

Faiham was later informed that the minister had filled out the necessary paperwork to compensate this man for his injury. “I know this is one small incident out of one million people and thousands of exploitations that is happening to the workers, but still, once you find something is happening, someone addressed something, one small drop creates the big scene. This one small thing sometimes give you inspiration for your work.” In this case, and hopefully many more to come, Faiham’s work made the lives of tea workers less abstract and brought these issues to the attention of changemakers.

By displaying his photos from the tea plantations at exhibitions, Faiham hopes to touch a wider audience with his work. His photo exhibitions are shedding light on an element of Bangladeshi society that many are unaware of. He remarks: “I have people come to me at the exhibitions saying, ‘oh I drink so much tea, 15 cups a day, but we never heard of the stories – we never knew that these are the people bringing the tea into our cup’. In that way I believe I am definitely trying to build a story on behalf of them and let people be informed about it.” Although, through my discussion with him it is clear that Faiham is most touched by the impact his images have on the tea workers themselves.

He describes how tea workers who attend his exhibitions are mesmerized seeing their own lives displayed in such a way. For many of them it is the first time they are seeing images of themselves and the first time the wider society has shown an interest in their lives. Some members of the tea community even host photo exhibitions when Faiham isn’t able to make it. Faiham describes how he only had to show them how to properly display the images and they now passionately carry on the project in his absence. This, for Faiham, is most significant. He is able to give a stage to these often marginalized parts of society and give the workers a sense of ownership over his Cha Chakra project.

As for a solution or first step towards helping these workers, Faiham is more reserved. “Like my project, a solution to the problems the tea workers face might evolve in an organic way”, he tells me. “Everybody has some sort of responsibility. But the solution should come in an organic way, not prescribed from the outside. People should understand their lives, the beauty of their lives, the demands of their lives… Development does not mean they have to be living in apartments or brick houses. We have to organically understand what is the best way which can provide a sustainable life for them. That’s why I believe the solution that the outside community is looking for should come in an organic way.” Much like the work that Fairfood does, Faiham’s work is giving light to the invisible workers behind our tea.

For more photo’s and information, visit faihamebnasharif.com